Why Quantum Security Isn’t Bitcoin’s Only Vulnerability and What the Data Really Shows

In late 2025, Bitcoin evangelist and MicroStrategy co-founder Michael Saylor doubled down on the narrative that quantum computing will ultimately make Bitcoin’s cryptographic defenses stronger, framing future quantum resistance as a maturation milestone for the world’s largest blockchain. While it’s true that quantum-resistant cryptography presents an important long-term milestone for secure networks, focusing exclusively on a future quantum threat can obscure a far more immediate, quantifiable risk on Bitcoin today the 1.7 million BTC already considered exposed under existing cryptographic assumptions.

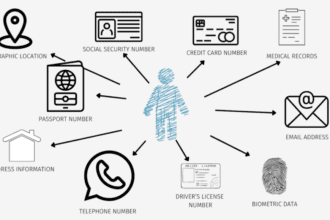

Over the past year, researchers, analysts, and on-chain observers have increasingly pointed to a critical blind spot in the broader crypto security conversation: not all Bitcoin addresses are created equally secure. Around 1.7 million BTC belonging to wallets that have reused public keys, employed weak address derivation methods, or were generated with early, less rigorous key-generation tools currently fall into a category where they could theoretically be compromised without even requiring powerful quantum computers. Simply put, these coins are sitting in addresses whose cryptographic “surface” isn’t as robust as the modern ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm) standards that currently secure most Bitcoin funds.

To understand the gravity of this situation, it helps to break down what Saylor and others mean when they talk about “quantum resistance.” In classical Bitcoin cryptography, private keys are mathematically tied to public keys through ECDSA. Bitcoin addresses that have never been spent from hide their public keys behind hash functions, meaning the network has never revealed the full public key on-chain. These unopened or cold addresses are relatively safe even powerful quantum machines would still need astronomical computational power to reverse these hashes. However, once coins are spent from an address, the public key becomes visible on-chain, potentially exposing those funds to future attacks if quantum-capable machines ever break ECDSA at scale.

This is where the current risk emerges: roughly 1.7 million BTC reside in addresses where the public key has already been revealed on-chain due to prior transaction activity. That’s not a future risk that’s a present technical reality. A sufficiently capable adversary with optimized algorithms, combined with advances in computing power (quantum or classical), could in theory attempt to derive the associated private key from the exposed public key. While today’s classical computers are far from achieving this, the existence of exposed public keys means these coins lack even the theoretical safety buffer that unopened, unspent addresses still enjoy.

Saylor’s recent comments highlight future improvements like quantum-resistant cryptography, which seeks to replace or augment ECDSA with algorithms designed to withstand both classical and quantum attacks. These upgrades are part of a broader roadmap in some parts of the blockchain community, including research into lattice-based signatures and hash-based schemes that are believed to be less vulnerable to the types of parallel computation quantum machines might offer. In theory, a quantum-hardened Bitcoin could become more secure than it is today, protecting future transactions even in the presence of exponentially more powerful processors.

But the emphasis on future hardening can distract from today’s structural security issues. Those 1.7 million BTC are concentrated in legacy wallets many dating back to Bitcoin’s early years when best practices around key reuse, multi-signature adoption, and address hygiene were not as well understood. Some of these coins belong to holders who have long since disappeared from the ecosystem; others are tied to early adopters or exchange cold wallets that reused addresses without anticipating future visibility risks. The result is a non-trivial slice of Bitcoin’s total supply that sits in a comparatively weaker security posture.

The implications extend beyond theoretical academic debate. If attackers target weak points in the network whether through future quantum machines or better than expected classical cryptanalysis those exposed keys are the low-hanging fruit. High-value targets like long dormant wallets, early miner addresses, and old exchange reserve addresses could be disproportionately tempting, since a breach would result in a large BTC haul with powerful financial incentives attached. These dynamics would play out not in some distant quantum future, but the moment computational capability crosses certain thresholds making the timing of cryptographic upgrades and address hygiene improvements a strategic priority for the network.

To be clear, the probability of a classical computer today breaking modern ECDSA keys even exposed public keys is effectively zero. The current computational costs and time required remain astronomically high. However, the Bitcoin ecosystem thrives on extreme improbabilities being treated as serious risks, precisely because the cost of failure loss of funds at scale is so significant. This mindset is what gives Bitcoin its reputation as a safe haven in digital asset markets. Treating exposed public keys as a ticking time bomb, therefore, is not alarmism but responsible risk management.

Saylor’s broader point that quantum computing ultimately will play a role in Bitcoin’s evolution is not wrong. Quantum resistance research is valuable, and preparing for an eventual era where quantum hardware could disrupt classical cryptographic assumptions is prudent. Many in the cryptographic and blockchain research community believe a move to quantum-resistant signature schemes is unavoidable if Bitcoin expects to remain secure in the very long term. But that transition would address a future class of threats, not the pressing risk posed by the existing stock of exposed keys.

This distinction matters because risk mitigation strategies differ depending on the nature of the exposure. For future quantum threats, research and algorithmic upgrades are essential. For present key exposure, the priority lies in encouraging best practices around address reuse, multi-signature wallets, and custodial policies that minimize long-term visibility of public keys. Users and institutions alike need to understand that security is multi-layered and contextual; focusing on distant threats while sidelining existing vulnerabilities creates blind spots that financial adversaries could exploit if conditions change.

Moreover, public discourse around quantum and Bitcoin can shape market psychology. Statements by prominent figures like Saylor can influence investor confidence, developer priorities, and community sentiment. If the narrative centers exclusively on future hardening without acknowledging current risks, it can lead to complacency about immediate security posture. Recognizing both present and future threats encourages a more balanced approach, ensuring the community invests in both quantum research and immediate best practices.

Developers in the Bitcoin ecosystem are already alert to these issues. Initiatives around taproot adoption, Schnorr signatures, distributed key generation, and hierarchical deterministic wallets all aim to improve privacy, reduce address reuse, and minimize exposed public keys over time. These steps are explored precisely because the community understands that security is not static; it evolves with usage patterns, threat models, and technological capabilities.

Thoughts, Michael Saylor’s emphasis on quantum resistance as a future hardening mechanism for Bitcoin highlights an important direction for cryptographic research. However, it should not obscure the real, measurable risk posed by the 1.7 million BTC currently sitting in exposed addresses. Addressing both present exposure and future threats will require coordinated effort from developers, custodians, wallet providers, and users. Only by acknowledging the full spectrum of risk from today’s legacy wallet hygiene to tomorrow’s quantum resistance can Bitcoin truly strengthen its claim to be the most secure form of digital money.