Why the Philippines is Pushing for Peace

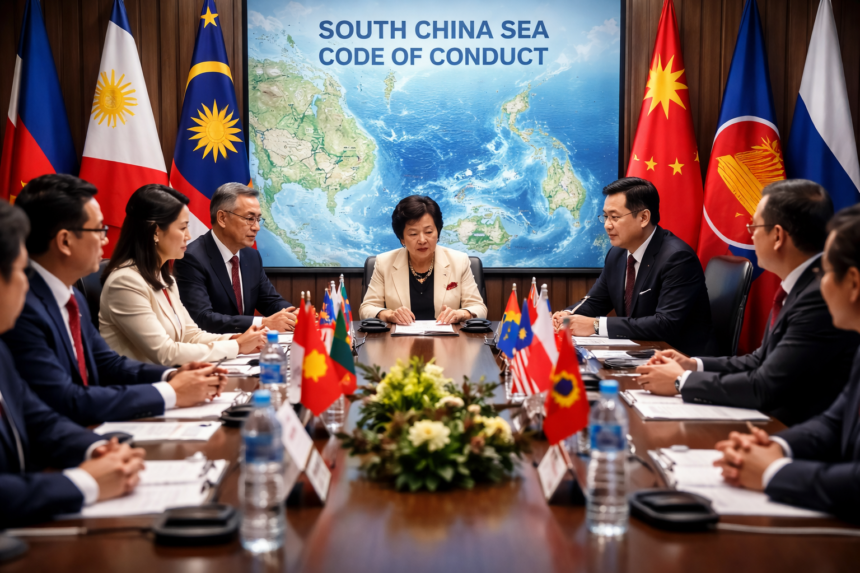

In 2026, a major diplomatic effort is underway in Southeast Asia as the Philippines, serving as chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), pushes to finally conclude a long delayed Code of Conduct (COC) for the South China Sea one of the world’s most contested maritime regions. This initiative seeks to establish clear rules and guidelines for behaviour in those waters, reduce tensions, and prevent clashes between rival claimants, particularly China and several Southeast Asian nations.

The South China Sea is a vast and strategically vital body of water bordered by China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. It is rich in fish stocks, potential energy resources and crucial shipping lanes used by global trade. Overlapping territorial claims, especially China’s expansive insistence on nearly the entire sea, have led to years of diplomatic tension, naval standoffs and confrontations at sea. A COC is intended to manage these disputes peacefully and prevent escalation into armed conflict.

What Is the South China Sea Code of Conduct?

The Code of Conduct in the South China Sea is an ASEAN China agreement meant to provide a framework for how claimant states behave in the disputed waters. It is different from past statements or declarations because the goal is to create a document that has clear rules, mutual expectations and, ideally, legal weight that guides the actions of all parties.

In 2002, ASEAN and China signed the Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, a broad statement that acknowledged tensions and encouraged peaceful resolution. However, it was non-binding and lacked specifics on how disputes should be managed. Since then, negotiators have worked sporadically toward a more detailed COC, but progress has been slow.

Today, the COC would ideally set rules on issues such as:

Freedom of navigation and overflight in the sea;

Prevention of dangerous activities like unsafe maneuvers or aggressive maritime operations;

Processes for consultation and de-escalation if disputes arise; and

Commitment to international law, particularly the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Why the Philippines Is Leading the Push

The Philippines assumed the ASEAN chairmanship on January 1, 2026, and its leadership has elevated the COC as a top foreign policy priority. Manila believes that a robust and binding agreement could bring much-needed stability to the region after decades of simmering disputes and incidents at sea.

Foreign Secretary Ma. Theresa Lazaro has stated that ASEAN aims to accelerate negotiations on the COC this year, proposing more frequent meetings from once every few months to monthly consultations to build momentum toward a conclusion by the end of 2026. China has not formally agreed to all of these meetings, but discussions with ASEAN states continue.

A central part of Manila’s position is that the COC should be legally binding and reference international law like UNCLOS, rather than merely being a loose political statement. A binding agreement would mean that signatories are legally obliged to respect the terms, which could help reduce misunderstandings and prevent dangerous maritime activities.

The Roots of the Dispute

The South China Sea dispute goes back decades and involves overlapping claims to maritime territory, reefs and islands. China asserts sovereignty over almost all the sea through its controversial nine-dash line, a claim rejected in a 2016 arbitration ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, which found no legal basis for China’s historic rights claims under UNCLOS. China does not recognise that ruling.

Other claimant states including the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan and Brunei base their claims on international law, particularly UNCLOS, which defines exclusive economic zones (EEZs) extending 200 nautical miles from a country’s shores. These differing legal interpretations have made resolving disputes extremely complex.

In recent years, numerous incidents, such as interference with Philippine resupply missions to naval outposts, water-cannon confrontations, and aggressive coast guard manoeuvres, have kept tensions high. These events underscore the urgent need for risk-reduction mechanisms that a COC could help provide.

ASEAN’s Challenges in Diplomacy

ASEAN itself is made up of diverse nations with differing relationships with China. Some members maintain close economic ties and prefer cautious diplomacy, while others are more vocal about confronting aggressive maritime actions. This diversity makes consensus difficult ASEAN decisions usually require agreement among all member states.

China, while participating in negotiations, has historically sought a non-binding code with flexible language. Manila and other ASEAN members prefer a stronger document that carries legal obligations.Finding common ground on issues like scope, definitions of self-restraint, and enforcement mechanisms remains a major diplomatic hurdle.

The long running negotiations, which have dragged on for more than two decades, show how difficult it is for a diverse group of nations and a powerful neighbour like China to agree on rules that could restrain behaviour in the disputed waters. But ASEAN’s continued engagement reflects a shared interest in preserving peace and stability.

The Importance of a Binding Agreement

A well-crafted, binding Code of Conduct could strengthen regional stability in several ways:

Reducing the risk of conflict: By outlining what actions are acceptable and unacceptable, the COC could lower the chances of incidents escalating into wider confrontations.

Clarifying expectations: Parties would have a framework about how to communicate and resolve disputes, which could decrease misunderstandings.

Providing legal confidence: Grounding the agreement in UNCLOS principles would reinforce the rule of law and support claims based on international legal norms.

Without clear, agreed upon rules, the South China Sea will likely remain a focal point of regional tension, shaped by power rivalries, national interests and the broader contest between China and other major powers.

The Road Ahead

Despite its challenges, ASEAN and China continue to meet to advance the COC. The Philippines’ leadership this year has injected urgency into negotiations, and there is cautious optimism that progress could be tangible. The success of this effort will depend on continued diplomatic engagement, sustained political will among ASEAN members, and China’s willingness to commit to an agreement that reflects shared interests in peace and cooperation.

If a COC is concluded and signed within the Philippines’ chairmanship year, it would mark a historic breakthrough for ASEAN and contribute to lowering tensions in one of the world’s most strategic maritime regions. Even so, implementation and enforcement will be critical to the document’s effectiveness and that will require trust, goodwill and ongoing dialogue among all parties involved.