Why the Latest Policy Changes Matter for Your Privacy, Data Rights, and the Future of AI Training

In late 2025, a significant update to X’s (formerly Twitter) Terms of Service quietly granted the platform and its AI models like Grok broad, perpetual rights to reuse, analyze, and incorporate user content into AI training and products, with few meaningful limitations. Unlike older terms that restricted reuse or required specific licensing rights, the new policy language explicitly states that by posting on X, users automatically grant the company and its partners a non-exclusive, royalty-free, worldwide, perpetual license to copy, modify, distribute, display, and use that content for any purpose including training AI systems without any opt-out mechanism. These provisions mark a major shift in how user-generated content is treated and raise serious questions about consent, compensation, and ownership in the age of generative AI.

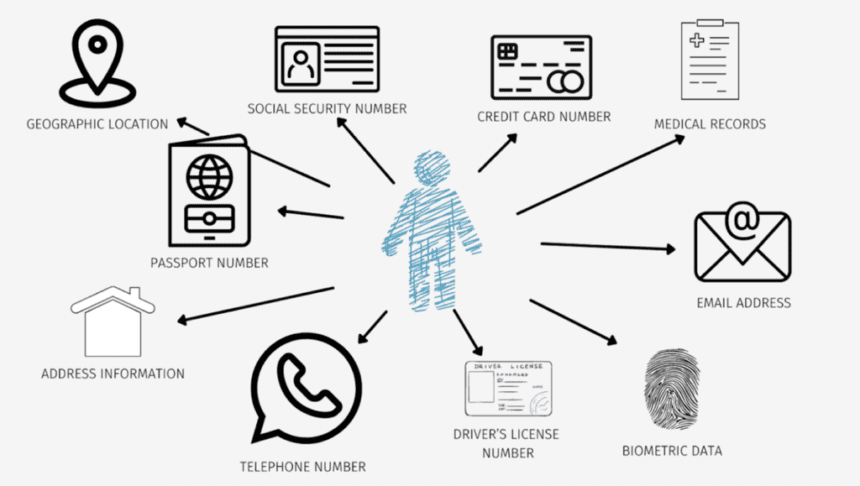

At its core, the controversy stems from the scope and duration of the rights X now claims over user posts, messages, replies, and creative works shared on its platform. Under the updated terms, content you post is not just published; it becomes part of an endless training pool for AI models like OpenAI’s Grok and potentially others. The license language is deliberately broad: it allows X to “use, reproduce, modify, distribute, display, create derivative works of, and otherwise exploit” user content in connection with AI and other technologies, forever and across all jurisdictions, with no requirement to seek further permission or pay creators. The changes apply automatically to all users upon acceptance of the terms which many users may overlook or not fully understand.

The implications of such licensing are far-reaching. For everyday users, this means that anything you post on X text, images, code, memes, or creative expressions can be ingested into AI training datasets and used to power future generations of generative models. Unlike traditional publishing, where creators retain intellectual property rights or can grant limited licenses, the new terms place extensive, perpetual use rights directly into the hands of the platform and its partners. Once content is posted, those rights cannot be revoked, and users have no built-in mechanism to remove consent even if they change their minds later.

This shift has alarmed privacy advocates, creators, and legal experts who argue that users are essentially giving away control of their work without meaningful compensation or choice. Under older versions of X’s terms, users retained more defined rights over how their content could be reused, especially in commercial contexts. The new policy, however, blurs that boundary, aligning more with data gravity for AI training than with traditional notions of copyright protection. If content is freely usable by AI developers indefinitely, questions arise about who truly owns derivative works, and whether creators should be compensated when their expressions contribute to powerful, monetized AI services.

One reason this change matters so deeply is because AI training data has economic value. Major AI models are hungry for high-quality input, and user-generated content from social platforms offers a vast, constantly updated source of real human language, creativity, and cultural nuance. When companies like X or its partners can legally ingest this data without paying royalties or negotiating licences, they extract value from everyday users without formal recognition. This raises ethical concerns about data labor, extraction, and the monetization of public discourse.

Critics point out that while users continue to own their original posts under copyright law, the new license effectively allows the platform to circumvent ownership controls by granting itself the right to use the content unboundedly. Copyright doesn’t vanish, but in practical terms, users lose much of the control that copyright is meant to provide. Once content is used in AI training, it can be embedded in models, regenerated in new contexts, and redistributed without any meaningful link back to the original creator or any compensation. This dynamic turns user contribution into a public good for AI development with creators receiving little more than exposure in return.

Some defenders of the updated terms argue that broad usage rights are a necessary trade-off for operating a public platform at scale. They contend that without legal clarity granting platforms and developers the ability to reuse content, AI innovation might slow or face legal challenges. In this view, an expansive license helps protect developers from copyright litigation while enabling rapid progress in generative models. However, the trade-off granting indefinite, unrestricted use rights with no user opt-out pushes this rationale into difficult territory, as it pits individual creators’ rights against corporate AI ambitions.

Another concern centers on how the terms are presented and accepted. Most users agree to platform terms without reading them in detail, yet those terms now serve as a blanket consent mechanism for far-reaching data use that extends well beyond social interaction. Unlike targeted licenses where creators can choose to allow or disallow AI training use or choose different levels of rights X’s newest policy treats all users the same, regardless of their preferences. If a user posts any content at all, their work can be absorbed into AI datasets forever.

This model also raises broader questions about platform responsibility and transparency. If AI systems are trained on user content without explicit, granular consent, what safeguards exist to protect privacy, prevent misuse, or allow creators to track how their data influences AI behavior? Some legal experts argue that without robust opt out options or clearer mechanisms for consent withdrawal, platforms risk legal challenges under emerging data-protection laws in jurisdictions like the European Union, where GDPR emphasizes user control over personal data.

At the same time, content creators and advocacy groups are pushing for new norms and legal frameworks that treat user contributions to AI training as a distinct economic category. Rather than blanket permissions, they propose tiered rights, opt-out mechanisms, and compensation structures that align AI training usage with fair licensing practices much like traditional media licensing but adapted for the digital age. If such frameworks gain traction, platforms may need to revise terms again and adopt more user-centric models of data use.

For everyday users, the takeaway is clear: posting on X now carries a potentially lifelong impact on how your words can be used by AI companies and developers. Whether you’re sharing a tweet, a thread, a piece of code, or creative art, that content can become fodder for models like Grok and others, without your ability to opt out or claw back rights. This represents a significant evolution in the relationship between social media, user content, and AI training ecosystems.

The debate over these updated terms continues, and legal challenges or policy revisions could still emerge in response to user backlash, regulatory pressure, or lawsuits. But for now, the new policy stands: if you post on X, you’ve likely given AI and Grok specifically permission to use your content forever. That reality not only changes the economics of how AI training data is sourced, but also how we think about privacy, ownership, and creative control in the digital age.